Learning From Cable: How FAST Platforms Are Finding New Growth In VOD

FAST platforms, once bastions of linear, are shifting to video on-demand (VOD). This means expensive UX upgrades and content rights. But it is likely the best way for dominant FAST services to remain at the top.

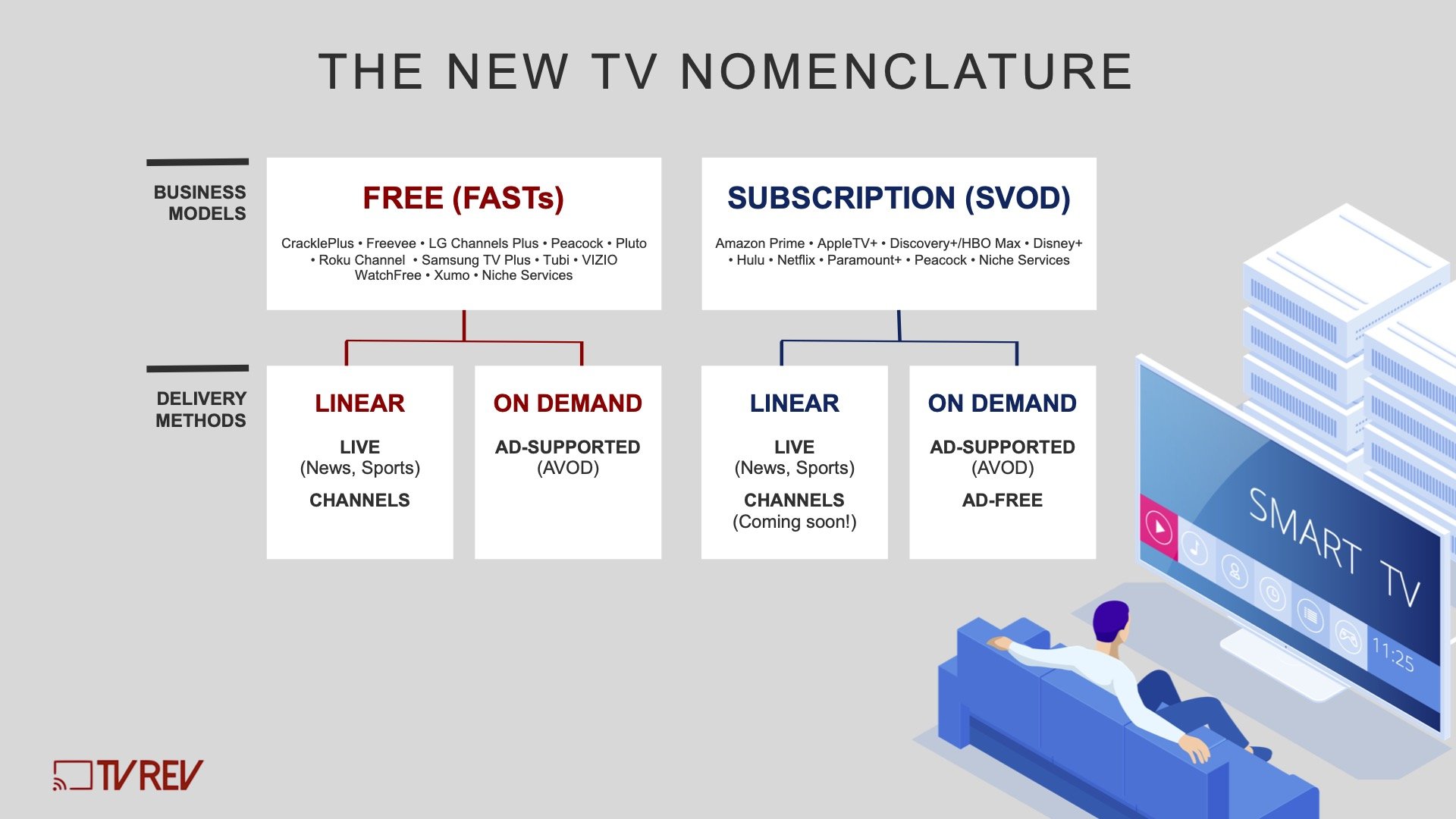

What’s changed? According to Nielsen’s The Gauge report, Tubi is consistently the leading FAST service in terms of “total TV usage”. While services like Pluto TV and The Roku Channel take linear-first approaches to FAST, Tubi stands out for its VOD-first strategy. Confusingly, each of the top FAST services deliver both linear and on-demand experiences. TVREV cuts through this confusion by separating the business model (FAST) from the delivery method (linear or on-demand).

The early years of FAST looked like a linear renaissance. Services mimicked the feel of cable. There was a sense that users craved the laid back ease of linear viewing. However, it is now becoming clear that FAST’s free-ness is more important than its linear-ness. FASTs initially launched linear channels because platforms like Pluto TV were able to buy linear rights to popular TV shows relatively cheaply. That created great value for viewers who liked obscure horror movies, 90s procedural dramas, classic sitcoms, or anything underrepresented on SVOD competitors, which at the time were essentially Netflix, Hulu, and Amazon Prime. Platforms like Pluto TV could then superserve niche audiences with “multiplex” style channels.

“Multiplexing” is an age-old TV strategy. Brands like HBO began launching spinoff channels in the 90s: HBO 2, HBO Comedy, HBO Latino, and more. This gave subscribers more choices. If they didn’t like the movie on HBO, they could flip to HBO 2 or HBO Comedy and maybe like that programming better. More bang for your buck. Think ESPN and ESPN 2. Or History and H2. The idea was to keep users in your ecosystem rather than allow them to switch to a competitor or worse, turn on their VCRs.

This strategy was a boon to cable for a decade or two until VOD took off. The pull of being able to choose exactly what to watch and when to watch it proved too strong to ignore, and by the early 2000s on-demand was on the rise.

Comcast, for instance, launched its on-demand service in 2003. Most major cable channels had TV Everywhere apps by the 2010s. It is clear that broadcast and cable devised on-demand options to combat DVRs and Netflix. Yet, this was half-hearted. VOD native streamers were ultimately given runway to provide users with better experiences than cable’s combination of multiplexing and on-demand could offer.

Today, FAST platforms take multiplexing to new heights, giving users hundreds of intentionally overlapping channels to choose from. Tired of FORENSIC FILES? Watch COLD CASE FILES instead. Tired of COLD CASE FILES? Watch UNSOLVED MYSTERIES. As long as viewers stay in that platform’s ecosystem, it doesn’t much matter which channel they are watching.

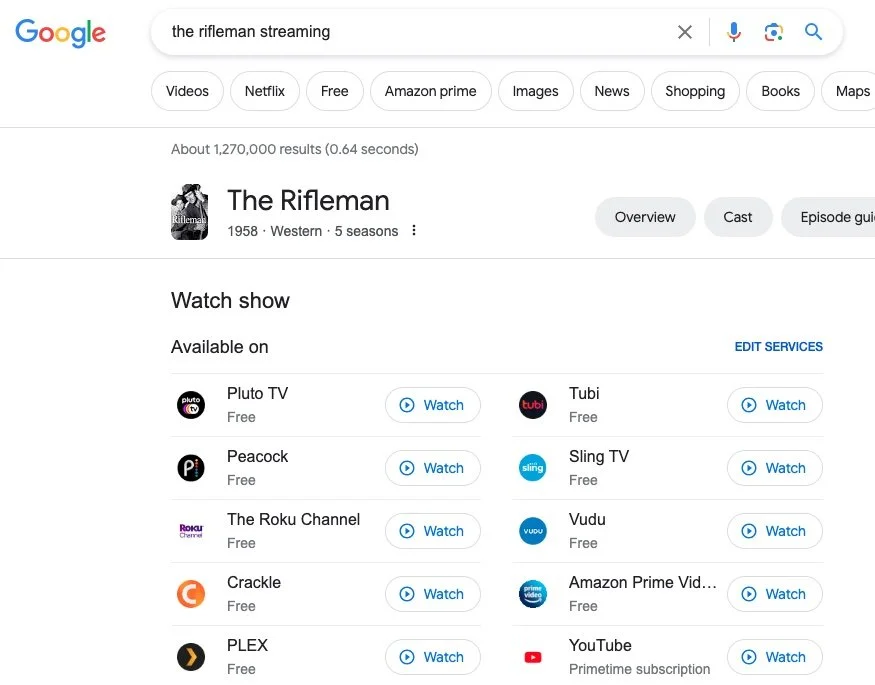

But this trick is once again losing steam to the inevitability of VOD. The marginal return of launching a new linear channel (multiplexing) is likely going down, as tends to happen in competitive environments. Easy-win type programming gets acquired quickly and ubiquitously. A title like The Rifleman is available on nearly every FAST service, turning content acquisition into a zero-sum game.

To combat this, acquisitions teams need to mine deeper and pay greater licensing fees to create new and differentiated channels. Pluto TV and Tubi can rely on IP from their parent companies, Paramount and Fox, respectively. But even this doesn’t come cheaply. The multiplexing model is reaching its ceiling, as it did with cable 10 to 15 years ago. And like cable before it, FAST is likely to find its next major boost from on-demand UX and library enhancements.

In that case, why aren’t all FAST services jumping headlong into VOD? Because, VOD is more complicated to pull off.

Linear remains preferable to on-demand in at least two cases:

If your linear experience is better. This is a UX issue. The linear electronic program guide (EPG) is easier to build and maintain than an on-demand experience. EPGs have been around since the 1980s. Viewers are accustomed to it. An EPG can be functional and pleasant with few bells and whistles. The VOD experience, meanwhile, needs to reach a higher level of sophistication before it is appropriately functional for users.

If the linear catalog is better. A FAST service shouldn’t push a VOD-first strategy if its VOD library isn’t at least as good as the linear offering.

In a media landscape of dwindling profitability and increased focus on cost savings, it could be considered prudent not to get sucked into a VOD-first strategy if you can’t guarantee a first rate experience. The UX and library demands on VOD are both seriously expensive. Yet, the history of VOD and linear suggests that on-demand is likely the direction users are heading in. We can see this in cable’s experience with multiplexing, on-demand, and TV Everywhere. When incumbents focus on evolving their linear-first experiences, they open the doors for VOD-native streamers to leapfrog competitors in popularity. In the long term, FAST is likely to continue to be a linear/VOD hybrid, only with linear supporting VOD rather than the other way around.